For the 189th issue of the Magazine House publication Hato yo! published January 1st 2000, movie director and screenwriter Shimako Sato leads a three way conversation between herself and her acquaintances, the anime and live action movie director Hideaki Anno, and manga artist Moto Hagio.

Together they discuss their respective admiration for each other’s work, Anno’s past statements on otaku, their takes on parent-child relations, how to escape puberty, and why Anno finds it scary to be around children.

To Me, There is 5 Ways To End a Story

Hagio: I got really into Neon Genesis Evangelion after it finished airing (laughter). I had been told by an acquaintance that Eva was a work that had “fans who were looking forward to watching the series so enraged by the developments in the final episode that they broke their TVs” (laughter). I wondered what could a work that evokes such strong emotions be like? I was really interested, so I borrowed the VHS tapes from a friend of Shimako-san’s, then I started watching.

Anno: I’m a big fan of Hagio-san’s manga, so when Shimako-san first said she could introduce us and arrange this meeting I was truly happy. The fact that you took an interest in Eva is an honor but… When I first heard “to me, there are five ways to end a story” I thought “as expected; amazing!” So after several twists and turns I finally reached a conclusion

Sato: Anno-san, when did you first encounter Hagio-san’s work?

Anno: The first one I read was They Were 11! during its serialization. In elementary school I read it at the Ear-Nose-Throat Doctor. I generally read manga at the waiting room there or at the barbers, since I didn’t really get any manga to read at home. When I read They Were 11! back then I was blown away. After that I read Hyaku Oku no Hiru to Senoku no Yoru [trans: Ten Billion Days and One Hundred Billion Nights, original story by Ryu Mitsuse]. My favorite work is Half-god [Hanshin]. The fact that such a meaningful story could be told in only 16 pages is amazing. I think Hagio-san is a genius storyteller, but her art is amazing as well. In middle school I thought that if I copied Hagio-san’s art I’d become better at drawing.

Sato: If you had also imitated her storytelling would that perhaps have changed Eva’s final episode? (laughter)

Saving the world, love and hatred

Anno: You know, I don’t have much interest in concluding a story.

Sato: Do you hate wrapping a furoshiki? [trans note: a traditional wrapping cloth]

Anno: No, it’s that I think you can do more with a furoshiki than tie it up pretty. Like break it or tear it to shreds, all kinds of things.

Sato: If we include all that, isn’t that still doing the act of wrapping?

Hagio: In your case Anno-san, I find your way of grasping the world unique.

Sato: For both Anno-san and Hagio-san, even with the differences between manga and anime you’re making a serialized work, right. When you make a long-form work, is the ending something that is already decided? Or is it something that changes?

Anno: For me it’s something like a live performance, and ends up gradually changing as I create the work.

Hagio: I’m a bit too careful, so I can’t draw if I haven’t thought of the ending. An exception is when I made Star Red. Otherworld Barbara which I made later also ended up becoming an exception

Anno: Star Red’s ending was magnificent. I was also influenced by Star Red. Actually, I’ve written some dialogue similar to the one in Star Red’s ending

Sato: Which of the characters do you like?

Anno: Well, the protagonist.

Sato: I like Elg. At first I thought he was a rather unreliable person, but he gradually came to play an active role. By the end he revived a dead planet through love.

Hagio: I also like characters like that!

Sato: When I watch Anno’s works like Eva I feel like you are more the kind of person who saves the world through hatred, what do you think?

Anno: I don’t know

Hagio: That feeling of uncertainty becomes the foundation of your storytelling doesn’t it? I come to think that that feeling is something so overflowing you can’t tie it all together.

Sato: It seems you have some differences when it comes to making a story, but I think one thing your stories have in common is perhaps parent-child relations?

Anno: That is true, Hagio-san. Your relationship with your mother appears in your work…

Hagio: When I was a child, my older sister was my mother’s favorite, I was always compared to her. It seemed my mother thought that compared to my sister I was unreliable so she always worried about me, even when I was into my thirties she’d tell me to quit making manga.

Sato: And that was during The Poe Clan’s heyday wasn’t it?

Hagio: (laughter) When I was watching Eva, something that really caught my attention was Shinji-kun worrying about whether or not he was useful to his father. Yet there was a distance from his father. During that time I was very interested in, to put it into words, “broken relations.”

Otaku Are Generally Uncool

Sato: Anno-san, in your work I think father-son relations is something that makes an appearance. Are there any real experiences behind that?

Anno: My family was normal. If I have a complex it would be that we were a poor family rather than a just normal one, and my father has only one leg. Regardless, I think stories about parents are the simplest to make, it’s easy.

Sato: So since Eva is a parent-child story it ended up like that?

Anno: What makes it easy is that we have some preconceived assumptions about [parent-child relations], “have you argued with your parents?” and such.

Sato: What appears in your work isn’t those things, but your own internalized problems don’t you think.

Anno: That appears to be it. As for my family we truly were the archetypical lower middle class household. My father was a good person. A sensible man. When you’re under circumstances like my father was you have to live sensibly or else you’re excluded.

Sato: So in opposition to that, you became an otaku.

Anno: That might be it. Your most important model for what normalcy is is your family. But I have a younger sister and she is exceedingly normal. She doesn’t read manga, there is nothing twisted about her at all.

Sato: And by twisted you mean?

Anno: That she’s not an otaku.

Sato: Anno-san, you’ve said that you hate otaku, haven’t you.

Anno: It’s not hate. It’s just that I think otaku are uncool. To otherwise not notice that you’re uncool or purposefully suppressing that fact makes me feel disgusted.

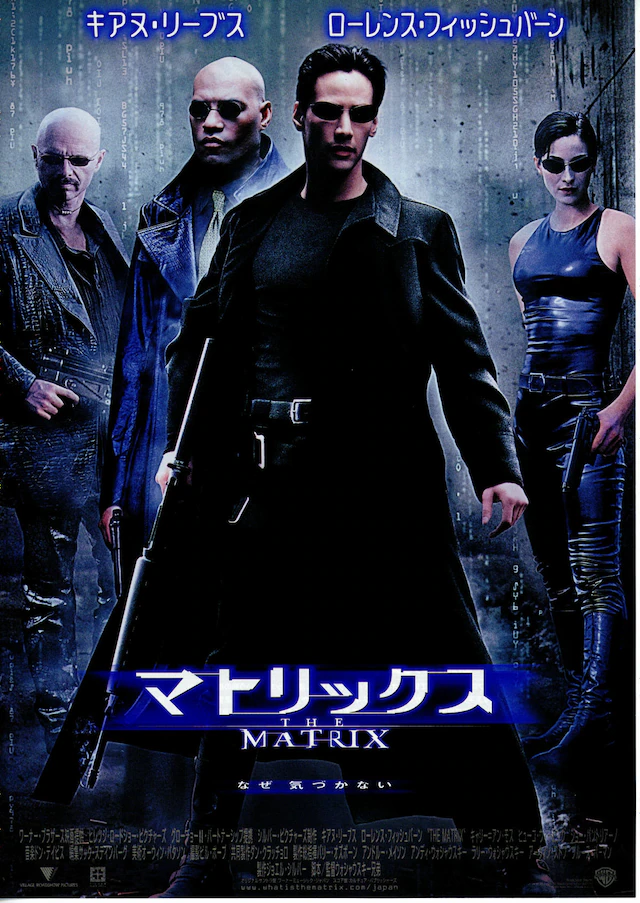

Sato: What about The Matrix? Isn’t that a cool otaku movie?

Anno: That one is also uncool.

Hagio: Even though Keanu Reeves is cool.

Anno: Keanu is cool. Because he is not an otaku. The otaku are the Wachowskis. They can’t get out of the confinements of their otaku-ism. So for example, even if they make something cool, part of it will for certain be otaku-like Even though I say this I don’t hate it. If I truly did I’d quit being an otaku.

Sato: Hagio-san, would you say your family was normal or was it perhaps affluent?

Joh (Hagio’s manager): Hagio-san and her mother actually have a similar biorhythm. It was perhaps due to that fact that Hagio rebelled by pursuing the path of becoming a manga artist.

Hagio: I might have been running away by drawing. But, if I had rebelled by becoming a delinquent I think it perhaps might’ve been more enriching to me as a person.

Anno: To become a creator is not something I think is a happy path to go down. In order to not be unhappy you have to work for dear life. At the very least create works as if you’re going back to zero [from the negatives].

Hagio: Is it a negative? Because you are an otaku?

Anno: Being an otaku is a huge negative. You make up for it either by relying on others or by producing creative works. With that said, I think my generation has it easier than yours, Hagio-san. This is an era where even old men read manga. My parents even now have no issues with my line of work. I appear in Asahi Shimbun, I appear on NHK, they have nothing to worry about. That is also why I will try not to ever refuse any coverage from my hometown newspapers.

Hagio: But don’t you think parents don’t truly understand? Even if I become famous, my parents will say; can’t you quit drawing manga? And just appear in the newspaper? (laughter)

Sato: But if you quit drawing manga you won’t appear in the newspaper. (laughter)

Hagio: In that context, a part of me still expects too much affirmation from my parents. Not externally but internally. Even if I appear in Asahi Shimbun I still end up thinking it’s not good enough.

Sato: The fact that you still worry so much about what your parents think at your age Hagio-san, it’s so strange.

Hagio: Yes, I think so too

Anno: Could it be that you have to become a parent to change that part of you that worries so much about what your parents think?

Sato: I don’t worry at all about what my parents think.

Anno: I also don’t care even a little bit. As far as I’m concerned, I’m bored if I get my parents’ approval. When I did Nadia: The Secret Of Blue Water for NHK I felt that feeling.

Sato: Do you have a replacement parent figure?

Anno: Well, a man without imaginary enemies is no good. For me right now, I think I want to make works that have Hayao Miyazaki beat.

Sato: Hagio-san, your worries might also be what gives birth to your works.

Hagio: That might be the case.

Sato: Anno-san, earlier, you said “you have to become a parent to change.” I personally don’t think if you don’t have children you can’t become an adult. I think that being an adult is being independent in everything you do. That’s why I think marriage or having children doesn’t change anything.

Anno: You can become a parent without being an adult. At 17 or 18 you could become a parent. To become a parent without even being an adult, that is the problem I think.

Sato: Do you consider yourself to be an adult, Anno-san?

Anno: I guess I’m a child.

Sato: I don’t consider my parents to be adults.

Hagio: I’m very discontent with the fact that my parents aren’t adults.

Anno: I’m not discontent.

Sato: For me realizing that my parents aren’t absolute adults was a relief during my middle school years. Until then I had played the role of an exemplary student, but when I realized that fact I stopped playing that role.

Hagio: So you’re a child who didn’t fit into your parents’ expectations. I was also a child who didn’t fit into my parents’ expectations, but the fact that they didn’t shrug their shoulders and say “that’s fine,” filled me with anxiety. I thought that if I become an adult I’d lose that anxiety. But I want recognition from people. I continue to request affirmation.

Sato: Anno-san, in Eva you portrayed children like this, but are you like this yourself?

Anno: The affirmation? Hmmm. That kind of thing changes with the project.

Hagio & Sato: ?

Anno: I don’t believe in the supremacy of the director of a work, but rather the work itself. What would be best for the work, I only base my judgment on the total. Although I won’t hand over the executive decisions.

Hagio: Manga is a one-man job, but with a movie there’s the director, the scriptwriter, the actors, etc. Each of them sees themselves as a leading part. Furthermore as living beings the things we do will sometimes diverge from the plan we made in our heads. The fun of living is discovering what those differences will be.

Is Eva The Rite of Passage That Will Get Us Through Puberty?

Sato: The movie Love & Pop that you directed Anno-san, the original creator Ryuu Murakami-san and yourself are both men, yet the story is about high school girls. I found that interesting.

Hagio: I thought that both of you wanted to be very similar to an archetypal girl. You said you wanted to see a part of puberty, and girlhood that you couldn’t control. After all, men aren’t just made up of boys. I believe that femininity and masculinity is something we have combined within us. Sort of androgynous.

Sato: The boys you create not having that vivid true-to-life quality to them I think is a representation of that. Anno-san, as a man, what do you think of the boys in Hagio-san’s manga?

Anno: I think they have empathy. I think what I like the most is that all the characters are smart. Because they have such a high intelligence it feels good to read.

Hagio: Like a washing machine right at the peak of its cycle, I want to leave my characters on the verge of that kind of critical point [of merger]. To be honest, the idea that once you’re past 30 you’ve become an old lady, that sense is something we’ve left behind.

Sato: I’ve found that when men become old they lose their ability to be nihilistic in their work, is it the same as that?

Anno: In the case of men, as you age, the world view [of your fiction] rather than your characters come to reflect your nihilism. You don’t aspire to be nihilistic, you yourself are becoming nihilistic. Your world view is what gradually utilizes nihilism. Isao Takahata, for example, is a nihilistic person. Nothing is born from being nihilistic. As nihilism is Plus-Minus-Zero, eventually your heart can’t be moved.

Hagio: A world that doesn’t change, isn’t that comfortable?

Sato: Even though in order to grow you have to fight. By asking like this, Anno-san, did you not experience puberty?

Anno: That might be it.

Hagio: I thought you were right in the middle of puberty.

Anno: I thought I’m losing it, but it might be puberty. Generally speaking, otaku don’t go through puberty.

Hagio: I thought otaku went through a prolonged chronic puberty.

Anno: It’s not what society ordinarily calls puberty.

Hagio: A never ending puberty, in this age, could it perhaps be because there are no more rites of passage?

Anno: Sure enough, you have to bungee jump. (laughter)

Hagio: A ritual to let your childhood die and then replay it, such a thing doesn’t exist now. Taking entrance exams may be the closest to [a rite of passage].

Sato: Don’t you feel like lately that age around 30 is when the coming of age ceremony actually happens?

Hagio: For that part, that’s when the stories takes on that role I think.

Sato: As a ritual?

Hagio: It’s not a ritual, but perhaps more intuitive? A trial run on a mock life. By that definition, I noticed Eva is just like that. I had an acquaintance who is a teacher from the Kyoto Steiner school. They saw the Eva movie in theaters. At that time they found the reactions of the people watching to be more interesting than the story. They had thought, isn’t it like we’ve all come to see the rite of passage which we all failed? I thought so as well “that’s right, that is interesting.” The rite of passage to become an adult after entering puberty, be it Gundam or Eva those stories put people in a position where they are observing the world, observing themselves, experiencing war and such.

Sato: Anno-san, were you considering all this…

Anno: I didn’t make it like that. But when I was making the movie I was thinking of this a little.

Hagio: When I watched Eva it ended up overlapping with the book Childhood [by Jan Myrdal]. It’s a book about a mother who can’t love her child. She thinks “I have to take care of this child”, but even so she can’t love him. I wonder what happens to children raised like this. Children learn from their parents. In truth there will be consequences for the parent, but the question on my mind was children who can’t find their place with the parent, where can they find their place instead? Although I thought you were such a person when you were making Eva, Anno-san. (laughter)

Sato: Speaking of, the other day you were on a TV show teaching grade schoolers about anime, Anno-san. What do you think of children?

Anno: I was scared of being in contact with children. I don’t understand the appropriate distance to take. I believe even the most casual thing an adult says mustn’t traumatize them, I end up becoming oversensitive. In grade school during still drawing class, I’d draw roof tiles and other detailed things, but humans moved around and I found it annoying, so I never drew people. Because of that my teacher said “this isn’t a child’s drawing,” which deeply hurt me. In the end, from that experience I think it was a part of the reason why I decided on working with drawing. Even though I opposed standardized education, I really felt the difficulty of dealing with not having a basic manual.

By the way, how much longer until Zankoku na Kami ga Shihai Suru [trans: A Cruel God Reigns] ends? I made a mistake. I wanted to read it all at once, right, so I refrained from buying it but… when volume 6 came out I ended up buying all of them.

Hagio: Oh yes, right. July next year I think.

Anno: Understood. Then the final collected volume will be out in the fall of next year. Hmm well that means I can enjoy it for another year. Understood.

Sato: Isn’t that great.

Translated by mod Juli, with assistance from two financially compensated native speakers.

A scan of the full interview raws has been added for posterity.

Sourced from 愛するあなた恋するわたし萩尾望都対談集 2000年代編 (Aisuru Anata Koisuru Watashi: Hagio Moto Taidanshuu Nisen nendai hen) The fourth entry of collection of conversations between Hagio and other manga artists or creative industry people. The books were published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha. Edited by Yuuko Anasawa with the collaboration of the shôjo manga research group Tosho no Ie.

If you have any questions about the translation or feedback after reading the raws feel free to let us know.