Edited by Arianna, Oscar, Nabilah, and Hilal

Content Warning: Mentions of pedophilia, pederasty, and sexual abuse.

Please read our introduction to this series here.

Setting The Stage

This article is the first of many entries in a series dedicated to exploring the genre labels encompassing male-male romance media marketed to women. We begin this endeavor by examining the early careers of two prominent artists in the history of male-male romance centric manga, Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, and their contributions to the formation of the shounen-ai genre. These two artists created standalone one-shots as rookies before eventually publishing their career-defining works. Their lives and careers intersected in a now highly-mythologized period of their personal histories. In investigating this period, we will highlight the works which remain embedded in the DNA of the commercial genre we know today as BL (Boys’ Love), male-male romance and erotica made primarily by women and marketed towards a predominantly female audience. We also touch on the media and literature which informed these works.

The late 60’s and early 70’s was a time of change in the world of shoujo manga, comics for girls. More female artists had gained prominence in the category throughout the 60’s, such as Hideko Mizuno, Miyako Maki, and Masako Watanabe. Publications dedicated solely to shoujo manga replaced the pre-war girls novelette magazines, setting the stage for a brand new generation of female manga artists to make their mark in the world of shoujo manga1.

Having debuted in the midst of a growing and changing manga industry, Takemiya (debuting in ‘67) and Hagio (debuting in ‘69), both 20 years of age, struggled to obtain parental approval to move to Tokyo to pursue careers as manga artists. Consequently, they each spent the first year after their debut working from their hometowns Tokushima and Ohmuta city. This proved problematic, as all the editorial offices for the major publishers were in Tokyo. After Hagio’s debut in Kodansha’s Nakayoshi, she struggled to find continued approval for her stories, as the publisher was very strict in their commitment to maintaining a theme for their publications2.

Meeting of the Minds

Hagio’s and Takemiya’s paths converged when Takemiya had to travel down from her hometown of Tokushima to Tokyo because she had struggled to complete her manuscripts for Shogakukan, Shueisha, and Kodansha. She was immediately put through two rounds of the now-retired practice of “canning,” wherein a manga artist is locked in a hotel room or ryokan by their editor until the manuscript is complete, often with intense supervision3. Hagio, having heard of this from her Kodansha editor during her own trip to Tokyo to pitch story ideas, asked if she could help Takemiya; this would be their first meeting. Through the meeting with Hagio, Takemiya was introduced to a reader, Norie Masuyama, with whom Hagio was staying for her trip4. Hagio and Masuyama came into contact after the publication of the standalone one-shot “爆発会社” (“Bakuhatsugaisha”) in Bessatsu Nakayoshi in 1969 when Hagio received a letter from Masuyama with whom she began mail correspondence5. Takemiya, likewise, introduced Hagio to her Shogakukan editor Junya Yamamoto, who bought Hagio’s rejected manuscripts and would go on to be a consistent supporter for Hagio6.

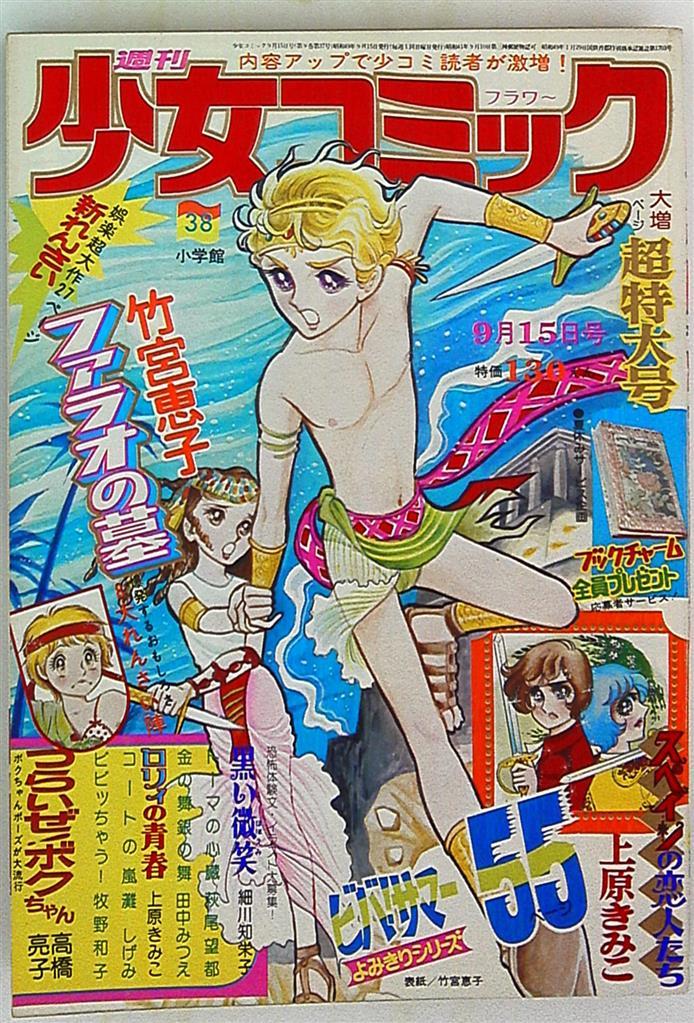

Hagio returned to Ohmuta City while Takemiya was able to gain her parents’ approval to move to the capital. Takemiya decided to work mainly with Shogakukan and its fairly new weekly shoujo magazine 週刊少女コミック (Shuukan Shoujo Komikku) Weekly Shoujo Comic, granting her parental consent and the freedom to pursue her career in Tokyo. While living by herself from ‘69-70 she grew closer to Masuyama, who was her own age and was out of school because she had failed to enter a prestigious music school per her parents’ wishes. Masuyama became a great source of influence for Takemiya in particular. Described by Takemiya as Tokyo born and raised, with great interest and knowledge in culture and media analysis, Masuyama was rather engrossed in the world of manga and shared Takemiya’s desire for “a revolution”7. This “revolution” entailed elevating shoujo manga into a more literary art form8. However, Masuyama was not a manga artist herself, hence she reached out to Hagio whose artistic abilities had impressed her.

During the period in which Takemiya was living by herself before moving to Ōizumi, she describes in her 2016 memoir, 少年の名は ジルベール (Shounen no Na wa Gilbert) The Boy’s Name is Gilbert, how when looking at her poster of Millet’s Daphnis and Chloe, inspiration suddenly struck and the image of a boy named “Gilbert” came to her9. She immediately called Masuyama to share the idea, and the two sat on the phone for eight hours discussing and sharing ideas for what would become Kaze to Ki no Uta (Song of Wind and Trees)10. They developed the story of Gilbert, a young boy sealed away at a countryside boarding school, where he is treated like “a male prostitute” by the students and teachers, but he would find camaraderie with a transfer student, a boy of mixed heritage who likewise experienced discrimination and ostracization from their peers11.The story would incorporate many elements from their shared interests and favorite literature.

It would take another six years of struggle against the Shogakukan editorial department before Takemiya could get her ‘life work’ into print. Takemiya and Masuyama felt that the way shoujo manga of the time rigorously conformed to the conventions of only having cute young female protagonists and simple boy-girl romances was a hindrance; they wanted not only more diverse themes, but also more male characters as the focus in stories. Additionally the magazine covers fronted by illustrations of cute girls were a point of contention for the two. As Masuyama said, even American girls’ magazines had boys on the cover, presumably because ‘girls like boys’12. It is still worth noting, however, that male models, and illustrations of couples that included a male character could sporadically be seen on the covers of Japanese girls comics magazines during this time, including Shoujo Comic. But solo illustrations of male characters were not common.

The careers of Hagio and Takemiya intersected for roughly two years (1970-72) in a period during which they cohabitated. This living arrangement began after Hagio finally moved to Tokyo, and Takemiya, who had lived all by herself since her move to the capital, craved company. They lived under the same roof, but in separate apartments at a rowhouse near Masuyama’s home in Ōizumi located in Tokyo’s Nerima ward, this space would be affectionately named Ōizumi Salon.

Masuyama recommended the literature and films that would later inspire and influence Hagio and Takemiya. Herman Hesse’s novels, such as Demian, Under the Wheel and Narcissus and Goldmund and movies like A Death in Venice (1971), Les amitiés particulières or A Special Friendship (1964) served as sources of inspiration. Takemiya and Masuyama, however, had already individually become fans of The Vienna Boys’ Choir, and Taruho Inagaki’s 少年愛の美学 (Shounen-ai no Bigaku) or The Aesthetics of Boy Loving. While Takemiya may have borrowed the word shounen-ai from Inagaki, her interpretation of shounen-ai differed in that it was not grounded in the idea of an older individual with a young boy, but rather the free love between two boys13. We will specifically address the pederast philosophy present in Inagaki’s works and their connections to the shounen-ai and BL genres in forthcoming articles.

Masuyama and Takemiya’s interest in homosexuality also led them to the legendary gay magazine Barazoku. Hagio has described how the two showed her issues of the magazine, but personally she found the content to be unattractive or ‘coarse’14. She instead understood the ‘beauty’ of male-male romance through the film A Special Friendship15. From this inspiration, she began what she thought would just be another one of her unpublished projects, namely Heart of Thomas16.

Budding Careers

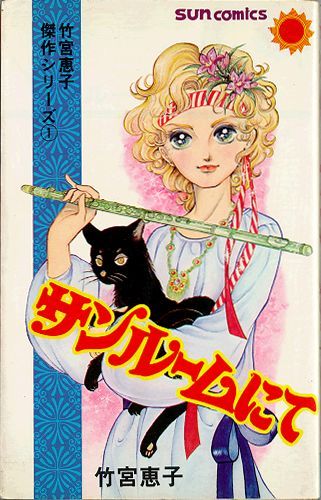

Takemiya hadn’t dared to bring up the topic of Kaze to Ki no Uta (henceforth referred to as Kaze Ki) or shounen-ai to her editors, having been certain that they would immediately dismiss it due to the male-male romance aspect17. But an opportunity to get a shounen-ai story published came in 1970 when she struggled to create a story she had already promised for Shoujo Comics’ new sister magazine 別冊少女コミック Bessatsu Shoujo Comic. Despite the title and a preview already being set and printed, she decided to steer off course and create her first attempt at shounen-ai. The story was titled “雪と星と天使と…” (“Yuki to Hoshi to Tenshi to..”), and was later retitled “サンルームにて” (“Sunroom Nite”) “In the Sunroom”.

“In the Sunroom,” which served as practice for Kaze Ki, would be notable for featuring the first male-male kiss in shoujo manga18. The story follows two young boys from different backgrounds, Etoile Rael and Serge Battour, and depicts them studying in the same school and developing romantic feelings for each other. The story culminates in a tragic end with Etoile’s death. The similarities to what would become Kaze Ki lie, for example, in Serge; in addition to sharing a name with Kaze Ki’s protagonist, also named Serge Battour, they also share Roma ancestry. Etoile also has many design features in common with Gilbert, such as his blonde hair, his very pale skin, and his tragic fate.

This guerilla tactic of delivering a story completely different from what was previously agreed on caused a conflict with the editorial department, in particular with Yamamoto, as “Sunroom” did not match the originally set title nor the already published preview19. Because there was no time for her to redo her manuscript or find a replacement, there was no choice for the editors but to let it run. In a later incident in which she was requested to do a Shoujo Comic cover, she drew an androgynous young boy instead of submitting the usual cute young girl. This did not please Yamamoto, but yet again, due to time constraints they had no choice but to let it run. According to Takemiya, these incidents dealt a blow to the editors’ trust toward her but paid off by way of supportive fan response through letters she received for “Sunroom.” A fellow manga artist with a similar interest in male-male romance, Ryoko Yamagishi, reached out to her as well20.

Hagio followed suit with her ‘made for publication’ version of Heart of Thomas; “11月のギムナジウム” (“Juuichigatsu no Gymnasium”) or “November Gymnasium” in 1971, which also ran in Bessatsu Shoujo Comic. The story is set in a German boarding school and follows the lives of Eric and Thomas, two young boys who share an uncanny resemblance–except for the color of their hair and eyes. While the relationship between the two is strained, Eric and Thomas are also drawn to each other until Eric’s sudden death. This tragic passing is accompanied by the revelation that the two boys are twins who were separated at birth. Apart from the relationship between Eric and Thomas, suggestions of male-male romance can also be read from the relationship between Thomas and Oscar. Oscar was a boy a year older who supposedly flunked to be in the same class as Thomas. Additionally, Thomas’ reputation portrayed him as a desirable “idol” among his all-male classmates who went as far as to compare him to “candy”, indicating further connotations of male-male attraction.

It is worth noting that Hagio describes no conflict in getting the story published, as Yamamoto usually accepted her manuscripts with little commentary. However, Hagio has noted also that Masuyama was rather displeased with the revelation that the boys were drawn to each other, because they were brothers21. From Masuyama’s displeasure with Hagio’s conclusion and with consideration of Masuyama’s media influence, one might presume that the aforementioned displeasure reveals that Masuyama perhaps expected that Hagio would not only share a vision of shounen-ai but also portray its themes in accordance with those expectations. Despite their creative differences, the two artists continued to build momentum for themselves, and friendship with fans and fellow rookies at the Ōizumi Salon, which became a meeting point for many young female mangaka.

In 1972, Hagio began an irregular serial of interconnected stand-alone stories, namely ポーの一族 The Poe Clan (1972-76), in the monthly Bessatsu Shoujo Comic. The Poe Clan was a story that spans centuries while following the 14-year-old immortal vampire Edgar, his sister Marybelle, and the boy Allan, who is turned by Edgar. While shounen-ai is not a label that succinctly describes the entire text, The Poe Clan can be loosely associated with the genre. These readings emerge from stories such as one in which a kiss between Edgar and another boy is depicted. Additionally, in the stories following Edgar and Allan as they navigate eternal adolescence together, they appear to exhibit an intimate bond, as in one story they even act as surrogate parents for a young human girl.

Diverging Paths

While The Poe Clan was working to prove itself as a hit among readers, tensions were brewing at the Ōizumi Salon. Takemiya found herself negatively compared to the skillful and diligent Hagio by their shared editor, Yamamoto, who found Takemiya’s career as a manga artist confusing22. Adding insult to injury, Takemiya’s 50 page manuscript of Kaze Ki drafted in January of 1971 was repeatedly rejected by publishers23. The comparison to Hagio alongside this series of rejections heightened Takemiya’s sense of insecurity about her abilities. In Takemiya’s account on the end of Ōizumi Salon, she merely remarks that she decided to leave when the lease was up toward the end of 1972, as the intense feelings of anxiety made it difficult for her to work24. The Ōizumi Salon subsequently dissolved, leaving Hagio and Takemiya to embark on their separate paths, although they still lived close to one another.

The one-sided tension from Takemiya towards Hagio eventually reached a boiling point in March 1973 after part one of The Poe Clan story “The Birds’ Nest,” which followed Edgar and Allan as they attended a German boys’ boarding school, was published. Hagio describes in her memoir, 一度きり大泉の話 (Ichido Kiri Ōizumi no Hanashi) (2021), how Masuyama and Takemiya accused her of plagiarizing the drafts of Kaze to Ki no Uta, claiming that several elements of Hagio’s work were too similar to Takemiya’s work in content and character25. They took issue with elements such as a boys’ boarding school by a river, scenes at a greenhouse, and even the motif of roses. These accusations are difficult to resolve at first glance due to their shared sources of inspiration and the commonality of these particular motifs in shoujo manga at the time. Masuyama additionally expressed dissatisfaction with Hagio’s representation and understanding of shounen-ai and bishounen or “beautiful boys”26. Following this incident, their careers grew rather distant but remained fairly professional.

When, in 1974, Shogakukan wanted a longer weekly serial to compete with the huge success of Shueisha’s Rose of Versailles by Riyoko Ikeda running in the weekly Margaret, Hagio was requested to do the competing serial. She stressed how she wouldn’t be able to sustain a several years-long serial like Versailles, but as she already had many pages worth of drafts for Heart of Thomas she presented it to the editorial staff27. Heart of Thomas (henceforth referred to as Thomas), a period piece that is much like “November Gymnasium,” which takes place at a German boys’ boarding school. But unlike “November Gymnasium,” Thomas opens in the way A Special Friendship ends, with a suicide. The story begins with news of the titular Thomas’ death, an event that would go on to haunt the characters Juli, the upperclassman whose love and attention Thomas tried to capture, and Erich, a transfer student who is the spitting image of the late Thomas. Described by Hagio herself as a coming of age story, Thomas is allegorical in its visuals yet textually explicit about its theme of all the many shapes of love–parental, romantic, and platonic–while also exploring the theme of abandonment by parents and subtly addressing an incident of sexual abuse28. These themes are explored as the characters face their traumatic pasts so that they may look forward to a brighter future29.

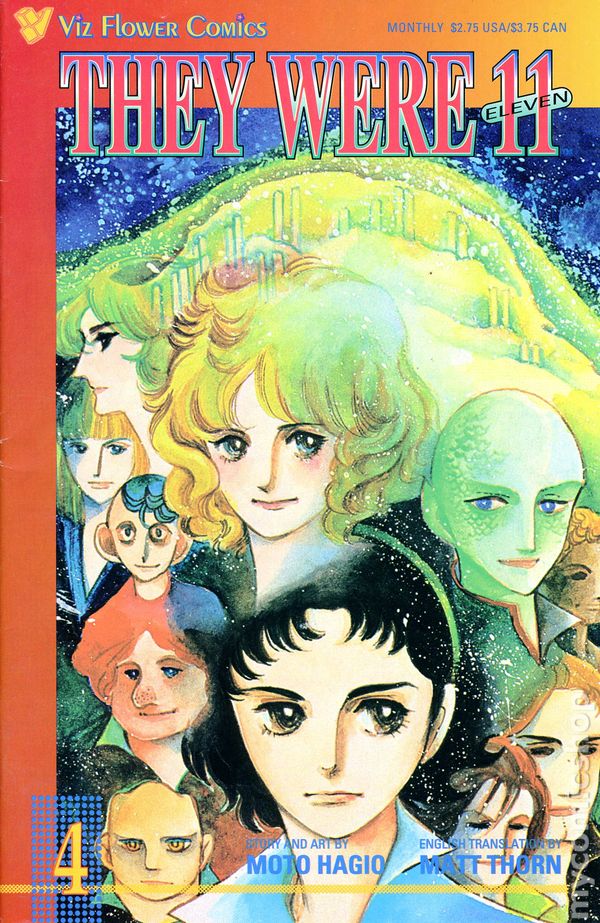

The series was greenlit but Thomas struggled to capture the attention of the young readers and remained at the bottom of the reader poll. Hagio was forced to buy more time from the editors on a week per week basis to be able to complete the story the way she wanted30. The tides turned when the first tankobon, or trade paperbacks, of The Poe Clan sold out of its 30,000 print run in three days, proving her wider marketability31. Thanks to the success of her sales, more attention from readers who otherwise would not have picked up Shoujo Comic were led to Thomas and she was able to leverage the success of Poe to complete a one year run32. By its final chapter, the series garnered a remarkable amount of reader attention, but still only peaked at 5th place in the reader poll. Readers who struggled to follow her work in the fragmented format of the weekly serial could again experience the story more cohesively as it was released in three trade paperback volumes in 1975.

Falling Behind Amid a Shoujo Revolution

The world of shoujo manga was transforming as attitudes were changing and an increasing number of authors embarked on ambitious projects and tackled topics previously considered taboo. But Takemiya, who was living with Masuyama during an emotional and professional slump, was lagging behind in the very revolution she wanted to participate in. Masuyama took on a role as Takemiya’s “manager” and assistant, while Takemiya was eventually assigned to a new editor who had recently transferred from Shogakukan’s boys’ manga magazine Weekly Shonen Sunday to Shoujo Comic.

The new editor, referred to by Takemiya as M-san, did not immediately dismiss and refuse Kaze Ki but instead said that if she made a serial that reached the top of the reader the poll , then Kaze Ki, the story she wanted so badly to put out into the world, could finally be greenlit. Up to this point, a significant roadblock in Kaze Ki’s road to publication was its explicit sexual content. From its initial draft up until the finished product, Kaze Ki opens with 14-year-old Gilbert in bed in the midst of a sex act with an upperclassman. These opening pages were far from the only explicit depictions of sex and nudity in the draft. Takemiya claimed that Yamamoto informed her of the fact that the magazine was delivered to the Japanese imperial palace, implying that the works published in Shojo Comic had to maintain an acceptable amount of “decency” and could not publish explicit sex scenes or content that directly featured graphic sexual activity33. Sex was referenced and depicted in shoujo manga before Kaze Ki; however, the representation tended to be much more abstract and less graphic – even kiss scenes had historically been considered controversial34.

With this promise from M-san finally giving her the opportunity to publish Kaze Ki, Takemiya could move forward with a sense of clarity and purpose.

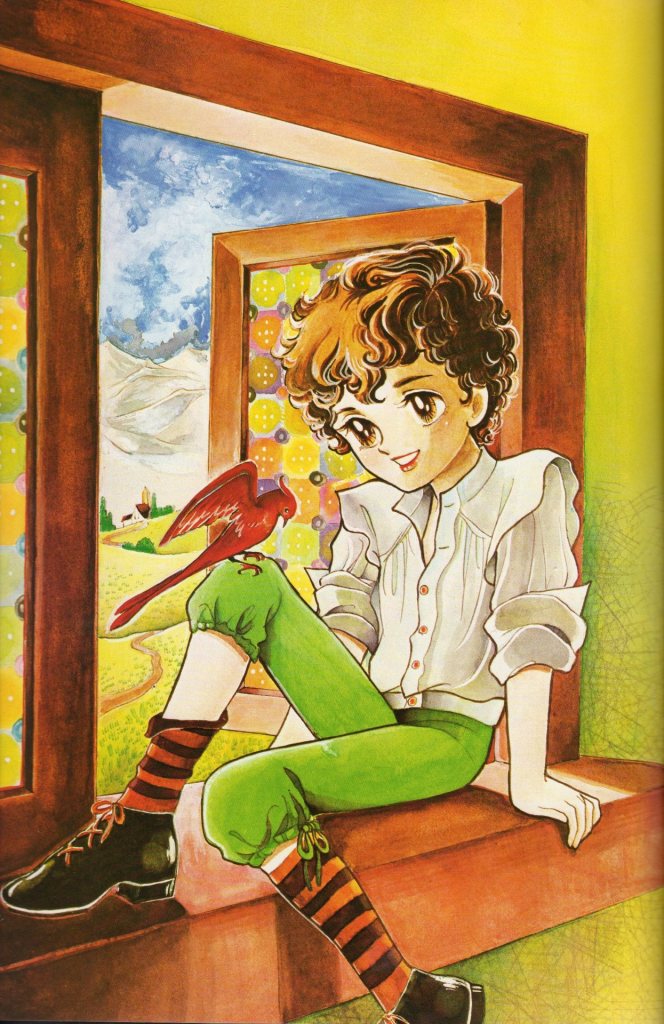

The serial that Takemiya developed with input from Masuyama started running in Shoujo Comic from 1974. The series she created to reach the top of the readers poll was titled ファラオの墓 (Pharaoh no Haka) The Tomb of the Pharaoh, a historical fantasy set in a fictionalized ancient Egypt. The story follows the conflict between Sariokis, the prince of the destroyed nation of Esteria, and Sneferu, the pharaoh of the conquering nation of Urjna. Takemiya chose Egypt as the setting for her work because she wanted to draw robed boys with their “pretty” skin exposed36. However, as it was published to prove her marketability to readers to her editors, it was not a ‘shounen-ai’ manga in the sense of there being any exploration of male-male romance; it instead focused on boy-girl relationships. Still, the aspect of beautiful male characters remained important. Takemiya studied Mizuno Hideko’s 星のたてごと (Hoshi no Tategeto) and 銀の花びら (Gin no Hanabira) in order to better present romance to readers. Takemiya’s preoccupation with a doomed or a forbidden relationship was still present in the story, with Sariokis falling in love with Sneferu’s fiancé and Sneferu falling in love with Sariokis’ sister. The recurring motif of forbidden love and tragic endings would remain present in Takemiya’s work.

The series successfully proved Takemiya’s wider marketability with a celebratory autograph event and noteworthy sales for the trade paperbacks of Pharaoh no Haka. While the ranking fluctuated throughout the series’ run, its popularity was sufficient in getting Kaze Ki greenlit in Shoujo Comic in 1976. Now considered a milestone in shoujo manga, but not without its controversies, Kaze to Ki no Uta is a period piece set in 19th century France that follows Serge Battour, the son of a French viscount and a Roma woman, an orphan when the story begins. The reader follows Serge as he enrolls at a boys boarding school. While the school has a colorful cast of characters, the main focus lingers on the young Gilbert Cocteau.

Gilbert is a 14-year-old boy who is continually sexually abused by both upperclassmen and teachers, and for this, he is shunned and mocked by his peers. Serge’s Roma heritage is utilized to make him an ‘othered’ individual, similar to Gilbert. Unlike Gilbert, however, he has to continuously deal with racist microaggressions and overt discrimination from his peers and strangers. Gilbert’s existence in the manga proves a focal point in the philosophy of ‘appreciation of male beauty’ because of the way Takemiya visually lingers over his body, positioning him as having been gifted with a profound beauty that captivate older men. The story goes on to rather explicitly deal with racism, child sexual abuse in and outside of the family, and the deep romantic and sexual bonds between young boys. It ran in Shoujo Comic until 1981 before moving to the newly established Puchi Flower where it ran until 1984.

Takemiya and Hagio continued to make successful stories in several genres, especially science fiction. Takemiya published Terra e… which ran in the boy’s manga magazine マンガ少年 Manga Shounen (1978-79), and Andromeda Stories written by Ryu Mitsuse (1980-81). Hagio’s exploration of sci-fi spans from They Were 11! (1975), to Otherworld Barbara (2002-05). But what may be most interesting about Hagio’s extended bibliography is her explorations of motherhood, gender, and the inner life of her characters. Masuyama is also not without her own bibliography; by choice she was an uncredited writer for Takemiya’s 変奏曲 (Hensoukyoku), a series of connected shounen-ai stories irregularly published from 1974 to 1985 set in the world of classical music. From 1990 to 1994, she also wrote three sequel novels to Kaze Ki titled 神の子羊 (Kami no Kohitsuji) that were serialized in JUNE under the pen name Norie Haaze.

Takemiya and Hagio were far from the only authors in the commercial space who made stories with predominantly male casts, explorations of bonds between boys or between men or even male-male romance; particularly noteworthy works of the era are Maya Mineo’s パタリロ! Patalliro! (1978-), Toshie Kihara’s 摩利と新吾 (Mari to Shingo) (1977-84), Yumiko Ōshima’s バナナブレッドのプディング (Banana Bread Pudding) (1977-78), and Yasuko Aoike’s エロイカより愛をこめて From Eroica with Love (1976-2012).

Looking forward

Despite having shared influences, Hagio and Takemiya possess extremely different philosophies towards ‘shounen-ai.’ In an interview with Aniwa Jun, Hagio states that boys are not only stand-ins for girls and sources of admiration for them, but also the very act of “becoming boys” is what girls aspire to37. In similar fashion, Hagio, when interviewed by Rachel Thorn, mentions that her choice in young boys as protagonists for The Poe Clan was because she considered them “non-sexual” and because the reader ages were around the same age as the characters38. In the same interview, she stated that while she considered making “November Gymnasium” a story set in an all-girls school, she found it came out too “giggly” and later mentioned that boys could say the lines girls could without it coming off as “cheeky”39. To modern and more politically informed readers this would obviously be considered misogynistic, and this was not lost onHagio herself. Akiko Joh, Hagio’s long-time manager, asserted that girls are very harsh with female characters but exceptionally lenient with male characters, which Hagio agreed to, discerning that she was still bound to stereotypes40.

Compared to Hagio’s ideals of boys as ‘non-sexual,’ Takemiya’s admiration of boys appears to have been in the form of young boys as objects of desire for herself and the readers as she focused deeply on the physical beauty of the boys themselves. While Hagio’s male characters are beautiful, their beauty is usually not constructed to evoke sensual desire or gratification from the reader, unlike Takemiya who focused heavily on the sexuality of the boys and portrayed them in sexually graphic situations. Because of her focus on sexuality and her connection to the shounen-ai magazine JUNE, Takemiya’s influence on the Boys Love genre and the doujinshi culture surrounding it is more singularly significant and will carry over to our exploration of the next era in Boys’ Love genre history.

As this period of Hagio’s and Takemiya’s career draws to a close, it is important to return to ‘shounen-ai’ etymology. To begin with, Takemiya and Masuyama labeled works of male-male romance as “knabenliebe,” a German word we can translate into English as pederasty; the Japanese equivalent of the word was likely lifted from Taruho Inagaki and his 1968 book 少年愛の美学 (Shounen-ai No Bigaku)41. When one breaks down the apparent meaning of 少年 = boy, 愛 = love, to someone with little to no knowledge of Japanese, this word may come across as innocuous or innocent; one might perhaps choose to accept Takemiya’s aforementioned interpretation of it meaning free love between young boys. Ambiguity aside, it is important to note that it typically refers to an ‘appreciation’ for the ‘transient beauty’ of young boys, or the idea of boys being ‘loved’ by adults, in particular older men. The term has fallen out of favor for some Japanese fans as it points to and evokes pederasty and pedophilia.

As we move away from these individuals, we can begin to explore the broader landscape of shoujo manga and anime. The ’70s was also a period of growth for the television medium of anime, and from this we can observe a fan culture emerging around the intersecting mediums of manga and anime that further develop community in a growing amateur scene. From this evolving amateuer scene, several new genres, styles, and communities were born. We will begin to explore the iconic semi-yearly event Comic Market that first began in 1975, the Doujinshi or “fanzines” distributed there leading to the coining of “yaoi,” and the very first commercial magazine dedicated to shounen-ai and aesthetic “tanbi” stories, namely JUNE.

– Juli & Oscar, with special thanks to Lys for providing material

Notes:

- F. L. Schodt, Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics (Kodansha USA, 2013), 97.

- Rachel Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview,” matt-thorn.com Shôjo Manga, last modified 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20120423171300/www.matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/hagio_interview.php.

- Keiko Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, (小学館, 2016), 16-18.

- Ryan Holmberg, “The Fukui Ei’ichi Incident and the Prehistory of Komaga-Gekiga,” The Comics Journal, last modified January 7, 2015.

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 16-18.

- Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 22.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 42.

- Ibid, 44.

- Ibid, 43.

- Ibid, 102.

- Akiko Hori and Mori Kisako, BLの教科書, (有斐閣, 2020), 20.

- Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 101.

- Ryan Holmberg, “The Fukui Ei’ichi Incident and the Prehistory of Komaga-Gekiga.”

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 103-105.

- Ibid, 107.

- Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 111.

- Ibid, 111.

- Ibid, 180.

- Moto Hagio, 一度きりの大泉の話, (河出書房新社, 2021), 148-149.

- Ibid, 150.

- Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Yuko Nagai. “NHK「ラジオ深夜便」6月2日の萩尾先生の回をテキスト化しました,” 萩尾望都作品目録, last modified 2014, https://href.li/?www.hagiomoto.net/news/2014/07/post-183.html.

- Ibid.

- Moto Hagio, The Heart of Thomas, (Fantagraphics, 2012), Introduction; Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Ibid.

- Moto Hagio, The Heart of Thomas, Introduction; Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 125.

- Schodt, Manga! Manga!, 101.

- Takemiya, 少年の名はジルベール, 196-197.

- Ibid, 202.

- Jun Aniwa, Aniwa Jun Taizen ( Tokyo: Meikyu 11, 2011), 43

- Thorn, “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Knabenliebe,” Collins Online Dictionary, https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/german-english/knabenliebe.

Bibliography:

Aniwa, Jun. Aniwa Jun Taizen. Tokyo: Meikyu 11, 2011.

Deppey, Dirk. “Mar. 27, 2007: The First Draft of History (some Revisions May Be Necessary).” Journalista – the News Weblog of The Comics Journal. Last modified March 27, 2007.

https://web.archive.org/web/20120224224003/archives.tcj.com/journalista/?p=321.

According to this article, Rachel Thorn claims that “as far as [she] knows, the first boy-on-boy kiss in a commercial shoujo manga” took place in “In the Sunroom”. In this same article, Deppey’s correspondence with James Welker confirms that the kiss in “November Gymnasium “was preceded by the kiss in in Takemiya Keiko’s ‘Sanruumu nite’/’In the Sunroom’” and claims that “In the Sunroom” was “the very very first shounen-ai manga,” although he remarks that he “wouldn’t put money on” that estimate.

Hagio, Moto. The Heart of Thomas. Fantagraphics, 2012.

Hagio, Moto. 一度きりの大泉の話. 河出書房新社, 2021.

Holmberg, Ryan. “The Fukui Ei’ichi Incident and the Prehistory of Komaga-Gekiga.” The Comics Journal. Last modified January 7, 2015.

https://www.tcj.com/the-fukui-eiichi-incident-and-the-prehistory-of-komaga-gekiga/5/.

Hori, Akiko, and Mori Kisako. BLの教科書. 有斐閣, 2020.

Kaoru, Tamura. “When a Woman Betrays the Nation: an Analysis of Moto Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas.” Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations, Spring 2019.

https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1747/.

“Knabenliebe.” Collins Online Dictionary. Accessed May, 2021.

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/german-english/knabenliebe.

Nagai, Yuko. “NHK「ラジオ深夜便」6月2日の萩尾先生の回をテキスト化しました.” 萩尾望都作品目録. Last modified 2014.

https://href.li/?www.hagiomoto.net/news/2014/07/post-183.html.

Schodt, Frederik L. Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics. Kodansha USA, 2013.

Takemiya, Keiko. 少年の名はジルベール. 小学館, 2019.

Thorn, Rachel “Matt”. “Hagio Moto: The Comics Journal Interview.” matt-thorn.com Shôjo Manga. Last modified 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20120423171300/www.matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/hagio_interview.php.

webDice Editorial Staff. “少年合唱の魅力:「花の24年組」として知られる漫画家・竹宮惠子氏、増山法恵氏トークショー.” webDICE. Last modified November 11, 2008. https://www.webdice.jp/dice/detail/1046/.

13 replies on “Takemiya & Hagio”

This was a super interesting read!! Looking forward to the next installation/post!

LikeLike

This only tangentially related and I’m sure the authors already noticed this but the author of the book “The Special Friendship” was a gay pedophile…He apparently went to form a relationship with a 12 year old actor at the filming of the movie based on the book, and even adopted him as his son at age 16. Their relationship was discussed in his memoirs…Also, not only was he a pedophile, but a conservative. Another French gay author of the time, Jean Cocteau (who the previously mentioned author admired) was a Nazi or Nazi sympathizer, and friend of friends of Hitler himself and thought Hitler was gay. As far as I can tell from both english and french wikipedia he wasn’t a pedophile. I still don’t understand gay conservatives or gay Nazis….but regardless, back to the actual topic. Clearly, Takemiya saw a kindred spirit in Mr. Peyrefitte. Takemiya’s sexual voyeurism of young boys is very sickening. Seeing her smile as an old woman; visibly proud of this work 50 years later is quite disturbing.

LikeLike

Also, I’m very confused by Hagio’s statement “that boys are not only stand-ins for girls and sources of admiration for them, but also the very act of “becoming boys” is what girls aspire to.” While I can understand the part about how male characters can get away with more (and we still see this today unendingly from women) but that statement is extremely perplexing…? The first half about boys as stand-ins for girls makes sense when we view the pederastic relationships or even just how strictly many BL works adhere to the submissive role in sex = submissive personality, but why is that a source of “admiration”? The second half is something I can’t interpret in any other way than a transgender lens because of my own identity….However, thinking about more, I read this essay/interview titled Actual Sexuality from 2000 between Kunihiko Ikuhara and Mari Kotani (which overall is a very strange and off topic meandering interview) but Mari Kotani suggests that the drive to make BL comes from it negating the idea that women are the passive and submissive ones, as far as I could understand? It’s VERY difficult to parse. But that isn’t really the same as “becoming men” and considering how Hagio saw shounen-ai as “non-sexual” the statement she made doesn’t corroborate the former suggestion…? I would appreciate a response and personal interpretation from this article’s authors, if possible!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your insightful response! We plan on addressing these concerns in depth in upcoming articles and greatly appreciate your inquiry. We are very much interested in exploring these authors’ relationships to gender and how that is reflected in their bodies of work, but in doing so we must be extremely mindful of modern conceptions of womanhood specific to Japanese society and the limitations we face as anglophone scholars. In regards to your concerns related to the book which preceded the film “The Special Friendship,” we agree with you in that it definitely demands greater scrutiny and so we plan to address this on our platform soon. Additionally, we definitely identify the need for our perspectives to be placed more prominently in the text to help readers identify our position on these sensitive matters, and will be moving forwards in our work with this in mind. If you’d like to voice your interests and concerns in greater depth please feel free to email us at fujoshimenaceCW at gmail dot com as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found this article just today, linked from a tweet. (One rightfully critical of anime and its fascist themes.) I follow someone on Tumblr who’s a big fan of Hagio and Takemiya, so I’m always curious to learn more. I’m glad I found this article!

I definitely agree with River, and finding out more of the background of Takemiya’s inspirations is startling but not surprising. Honestly, when I started diving more into BL, but mostly early shonen-ai, it was pretty disturbing to see the patterns and influences. And it’s no different with Takemiya. It would be interesting to find more articles and essays that discuss that side of shonen-ai and BL’s history.

As a Black, queer woman who got into BL fairly young because of my queer, friends of color around me, it was always a very mixed experience. The BL I started with was mostly 90s and early 00s stuff, and going back to these early works, it’s really harder to take in. I feel like so many fans of Takemiya, and even Hagio, really don’t examine how these two were so fascinated by Europe and thus, European boys. The way White, European boys are put on a pedestal by them is hard to take in now as an adult, and when I see those 70s and 80s manga with Egypt (by them/Takemiya, especially) as the backdrop and characters so whitewashed there as well, it’s hard to confront. I can’t bring myself to enjoy their works, even when appreciating and valuing their role in shonen-ai, BL and shojo manga.

Given your analysis and background here though, and your response to River, I am looking forward to the next piece! It’s all fascinating to take in, and certainly creates some topics for me to grapple with myself whenever I enjoy and/or examine BL.

LikeLike

This was a truly interesting read. I am glad that you guys are exploring and shedding light on how things unfolded, most of this was truly brand new information for me.

Reading the plot of Gilbert disgusted me. What was going through Takemiya’s head to passionately keep trying to publish it, and how proud she is even 50 years later.

However, as I am writing this comment I remembered how I came across the same plot (kinda it didn’t involve teachers) in other bl works when I started reading 10 years ago, namely: Michiru Heya (spin-off from Kami-sama no Ude no Naka) by Nekota Yonezou and all of this got me thinking just how much has Takemiya influenced others.

Are you guys also going to discuss the recurring deaths/suffering in works?

Regardless, thank you for including the references in hyperlinks, I will go through them at some point. I look forward to your upcoming articles.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment! We are currently working on upcoming articles on that will touch on narratives of same-sex romance and their aesthetics of recurring death and suffering across manga.

LikeLike

This was a wonderful article, that I just found. It especially interests me to see these manga discussed in such a researched and academic manner, something I’ve tried to do (my latest project involves interviewing women who read shoujo manga in the 60s and 70s and what the experience was reading them as new serialized works–how it was different, for example, to read KazeKi in installments over years and years. Already one interesting thing–several woman have said that in their classes when they’d discuss manga it wasn’t unusual to find that some of the boys were reading KazeKi as well as other shoujo works, and found them just as interesting, something that goes against much anglo discussion of their readership.)

I hate to comment years after the fact (though I do think that River especially, is giving a reading I can’t get behind, as someone who finds these works personally very cathartic) however I did want to make a quick reply to the above comment:

“Are you guys also going to discuss the recurring deaths/suffering in works?”

So often when I see a classic shoujo work with queer characters or themes, even when it’s positive, there has to be the caveat that it does end in tragedy (though I don’t personally think Thomas does.) Inevitably it is then mentioned how this is akin to the Western “kill your gays” trope, where gay characters had to be killed by the end of the work–as opposed to most straight characters.

But I think when discussing 1970s shoujo manga, in particular, this is a false equivalency. The fact is, aside from romantic comedies or aspirational sports shoujo manga, nearly all dramatic shoujo manga in the 1970s did end in tragedy, or at least had a lot of suffering in them. This is not unique to manga focusing on same sex relationships, but is largely true across the board. That was what was popular (and as a teen, myself personally, I definitely loved a good sad work.) It was not something that singled out “queer” narratives (for lack of a better word) and is unfair to read it that way.

LikeLike

I have this hypothesis that much of the rape fantasy seen in the yaoi genre (be it orginal manga or fan doujinshi) originated from Kaze Ki No Uta, and it stayed a hypothesis because I didn’t know how to prove it. Thus, I’m very grateful for the essays on this WordPress and can’t wait to read more.

LikeLike

Also, I’m hoping to learn about the history of the label “fujoshi” from this.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comments! We are steadily making progress on subsequent articles that will come to cover this topic.

LikeLike

[…] mangaka considered part of the Forty-Niners is Keiko Takemiya, who created the yaoi story In The Sunroom. Published in 1970 in the shoujo magazine Bessatsu […]

LikeLike

[…] other mangaka thought-about a part of the Forty-Niners is Keiko Takemiya, who created the yaoi story In The Sunroom. Printed in 1970 within the shoujo journal Bessatsu […]

LikeLike